http://www.salon.com/politics/feature/2000/10/13/texas/index.html

- - - - - - - - - - - -

By Alan Berlow

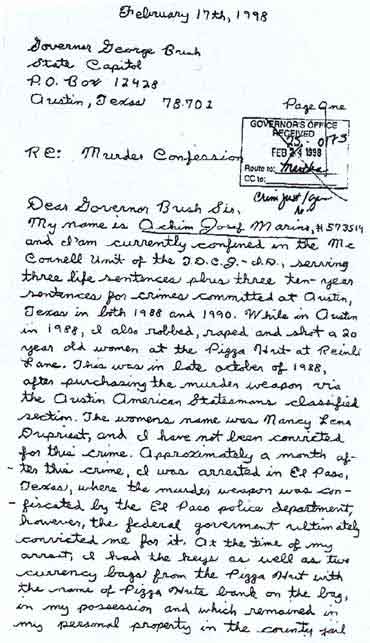

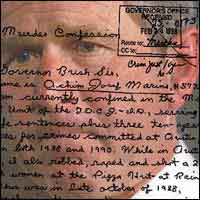

Oct. 13, 2000 | On Feb. 25, 1998, the office of Texas Gov. George W.

Bush received

an extremely unusual letter. Handwritten in curly script across the

top of the first page, just

above the salutation -- "Dear Governor Bush Sir" -- were the words

"RE: Murder Confession."

In the four-page letter its author, Achim Josef Marino, a 39-year-old

state prison inmate

serving a life sentence for aggravated robbery with a deadly weapon,

described how he

had "robbed, raped and shot" 20-year-old Nancy DePriest at a Pizza

Hut in Austin in

October 1988. Marino explained that at the time of the murder "I was

insane," and that

since then he had undergone a "Christian conversion" and "spiritual

awakening" and was

fully prepared to be executed for killing the young woman.

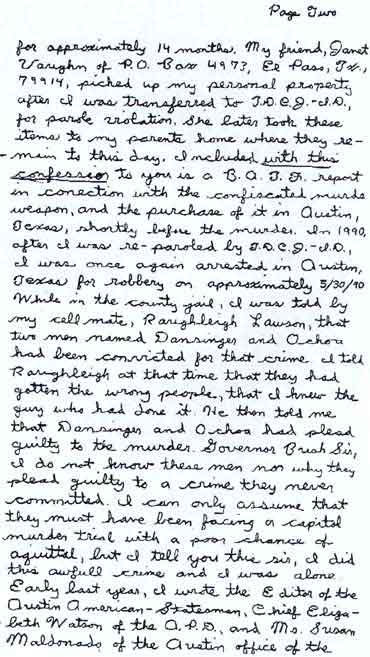

Perhaps most startling about Marino's letter was his assertion that

two innocent men were

serving life sentences for a crime he himself committed. "Governor

Bush Sir, I do not know

these men nor why they plead [sic] guilty to a crime they never committed,"

Marino wrote,

"but I tell you this sir, I did this awfull [sic] crime and I was alone."

Presented with evidence about a murder in the form of a confession and

the possibility that

two innocent men had been languishing in a Texas prison since 1988,

what did Bush do?

Nothing, according to Bush spokesman Mike Jones. Jones said the governor

receives more

than 1,400 letters from prisoners each year and, although he cannot

recall ever receiving

another murder confession by post, he insisted the letter was almost

certainly not brought

to Bush's attention. It was referred instead, Jones said, to the governor's

general counsel

and criminal justice staff, none of whom responded to Marino. Nor did

anyone from Bush's

office follow up on the matter with the Austin police, district attorney

or, as Marino himself

suggested in his letter, the two men convicted of the crime and their

attorneys.

According to Jones, "no additional action was taken by us" because Marino

wrote in his letter

that he had already referred his allegations to the district attorney's

office and the police. Bush's

office took Marino at his word. "There was really no other role for

the governor's office," Jones said.

Rosemary Lehmberg, first assistant district attorney for Travis County,

confirmed she received

no communication from Bush's office concerning any of Marino's claims.

"I think I would know

about that," she said. "I'm not aware of any contact."

Long after Marino wrote Bush's office, according to Lehmberg, her office

finally began looking

into the case. Lehmberg added that the Austin Police Department has

also been looking into the

allegations for "some time." A spokeswoman for the Austin police said

the department does not

talk about "ongoing homicide cases."

The possible existence of Marino's letter to the governor was first

reported a few weeks ago on

KVUE, the Austin ABC-TV affiliate. Salon was able to obtain a copy

of the letter from the

governor's office. (The office initially told reporters that it had

no copy of the confession, before

it was pointed out that the office was misspelling Marino's last name.)

Although Bush's office was under no legal obligation to turn over evidence

relating to the crime,

its failure to do so raises serious questions about the diligence of

Texas' highest law enforcement

authorities. Austin attorney Bill Allison represents Christopher Ochoa,

one of the two young men

whom Marino alleges were wrongly convicted for his crime. (The other

is Richard Danziger.)

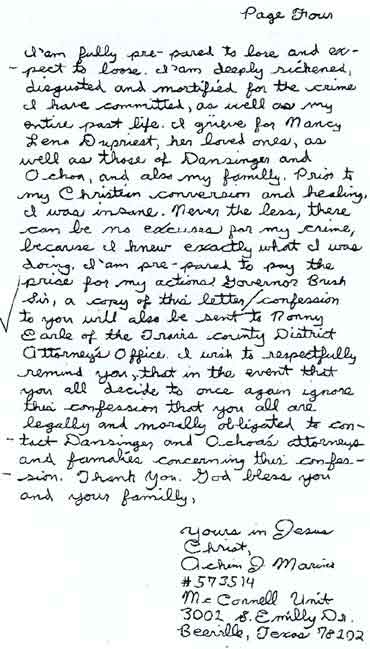

According to Allison, Bush's office had a clear obligation after receiving

the confession in the mail:

"They should have turned it over to law enforcement."

Marino, who has been convicted on three charges of assault with a deadly

weapon, felony possession

of a firearm and sexual assault, can hardly be held up as a model of

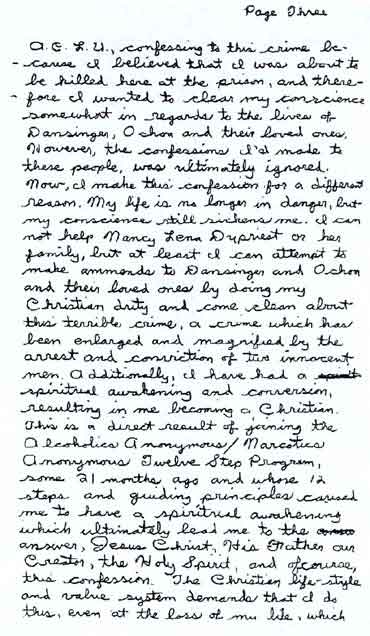

virtue. But in the conclusion of

his letter to Bush, Marino took a moral position difficult to disagree

with: Bush was "morally obligated

to contact Dansinger [sic] and Ochoa's attorneys and famalies [sic]

concerning this confession."

The disclosure about Marino's letter and the failure of Bush's office

to act on it comes at a time

when the governor's criminal justice record has been under intense

scrutiny. In June, the Chicago

Tribune reported that among the 131 men and women executed under Bush

up to that point, 40 were

condemned in trials where the defense attorneys presented no mitigating

evidence or only one witness

during sentencing, while another 29 went to their deaths based in part

on testimony by a notorious

state-financed psychiatrist, Dr. James Grigson, whom the American Psychiatric

Association found

unethical and untrustworthy.

To date, Bush has signed off on 145 executions, including several in

which troubling questions have

been raised. The most prominent recent case was the June execution

of Gary Graham, who was

convicted on the basis of testimony from a single witness, and executed

even though exculpatory

witnesses were never allowed to testify on his behalf.

Bush has consistently touted Texas' death penalty procedures, most recently

in his Wednesday

debate with Vice President Al Gore, in which he suggested that capital

punishment is the best way

to deal with "hate crime" homicides. Bush has stated that "there is

no doubt in my mind that each

person who has been executed in our state was guilty of the crime committed"

and that all of his

state's condemned prisoners have had "full access to the courts ...

and to a fair trial."

The two men Marino claims took the fall for his crimes were not sentenced

to death but to life in

prison because of the peculiar way in which the case developed. But

like those heavily scrutinized

Texas death penalty cases, the convictions of Ochoa and Danziger raise

profound questions about

justice in the Lone Star State.

Ochoa's case never came to trial because he confessed to murdering DePriest.

But University of

Wisconsin law professor John Pray insists Ochoa's was no ordinary confession.

Pray's nonprofit

research group, the Wisconsin Innocence Project, undertook its own

investigation of Ochoa's case

last year. "Ochoa confessed because of threats that if he didn't he

would receive the death penalty,"

Pray said. "What this says about the death penalty is that it corrupts

the system even in cases where

a defendant wasn't sentenced to death. It can create a situation in

which an innocent person will

plead guilty" to save his life. Pray, who along with Allison is one

of the attorneys representing

Ochoa, said his client was also threatened by Austin police officers

with physical violence if

he refused to confess.

Authorities in the district attorney's office would not discuss the case.

Allison said there are actually three Ochoa confessions in which "the

facts kept changing" and

were "getting better and better" from the state's point of view. The

attorney said the confessions

show how police hammered away at an apparently innocent man until they

got him to say what

they wanted. In the first confession, asserted Allison, "Ochoa basically

said, 'Somebody else did it

and told me about it. In the second confession, Ochoa's response was,

'I participated,' and in the

third, it became, 'I did the shooting.'"

Fortunately for Ochoa and his co-defendant, Richard Danziger, DNA evidence

from the rape of

DePriest was preserved and, following requests from the Wisconsin Innocence

Project earlier this

year, the Travis County District Attorney's Office agreed to have it

tested. Although the district

attorney has not released the results of that test, Allison said he

is confident they will confirm an

earlier test conducted by the state's own lab that demonstrates Marino

was telling the truth: that

he was the one who raped DePriest. The test showed that the DNA discovered

on the victim did

not match Ochoa's or Danziger's. It did, however, match Marino, the

new focus of the D.A.'s office.

Marino's story is further substantiated by claims he made about physical

evidence in his letter to Bush.

Marino said that keys from the Pizza Hut and two bank money bags from

the restaurant could be

picked up from his parents' home. Sources close to the investigation

say police did recover the

evidence exactly where Marino said it would be.

According to his attorneys, Ochoa, who had no criminal record prior

to his arrest on the murder

charge at age 22, was afraid for years to assert his innocence because

he thought prosecutors

might retaliate and seek a death sentence.

Danziger, who was 18 when he was arrested while on parole in connection

with a forgery conviction,

maintained his innocence throughout his 1990 trial, insisting witnesses

against him, including homicide

detectives, were lying. He is currently confined to a prison mental

institution. After his homicide

conviction, he had no legal representation until Oct. 6, when the state

appointed him counsel as

it was considering the second DNA test of Marino.

Marino claimed on the KVUE broadcast that he has confessed the details

of the murder to various

public officials -- including Bush -- in letters dating back as far

as 1996. The state, meanwhile, still

has not appointed him a lawyer -- even though his confession could

subject him to a death sentence.

Refusing to comment directly on the case, assistant district attorney

Lehmberg said, "He's not charged

with anything for one thing; he's here from the penitentiary where

he's been convicted, so there's

nothing pending against him."

Letter:

http://www.salon.com/politics/2000/10/13/prison_letter/index.html

"Dear Governor Bush Sir:

I did this awfull crime"

This is the letter Achim Joseph Marino sent the Texas governor

more than two years ago.

- - - - - - - - - - - -

Oct. 13, 2000